EAST BREIFNE O’CLERYS

EAST BREIFNE O’CLERYS

and their Clarke descendants

By Patrick Clark

his is an abridged version of the paper written by Patrick Clark.

In the sixteenth century, a minor branch of O’Clerys was among landholders of the principality of East Breifne, an Oireacht (lordship) ruled by O’Reilly dynasty “these O’Clerys, a sliocht (kindred family group), served the O’Reilly taiosigh (chieftains) as warriors and horsemen (mounted lancer) and Kerns (lightly armed foot) The English labeled such Irish combatants as ‘swordsmen.’ County Cavan Claries were descended from these O’Clerys.

Background

Government records documented this lineage’s forefathers of O’Clerys had been Connacht kings. Their aristocratic Tír Chonaill (Donegal ) cousins, lords of Cill Bharrainn (Kilbarron), were hereditary historians to the Uí Domhnaill (O’Donnell) Cavan O’Clerys became distinguished for literary attainments and the O’Clerys pronounced their surname O’Clayry or O’Clayrigg. Their patriarch, Tomás O’ Cléirigh (Thomas O’Clery), migrated to the territory towards the end of the thirteenth century, when Anglo- Norman invaders forced the Uí Cléirighs to leave districts in north-east Kilmacduagh, their ancient patrimony in south County Galway, near present day Gort.

Gaelic Refugees

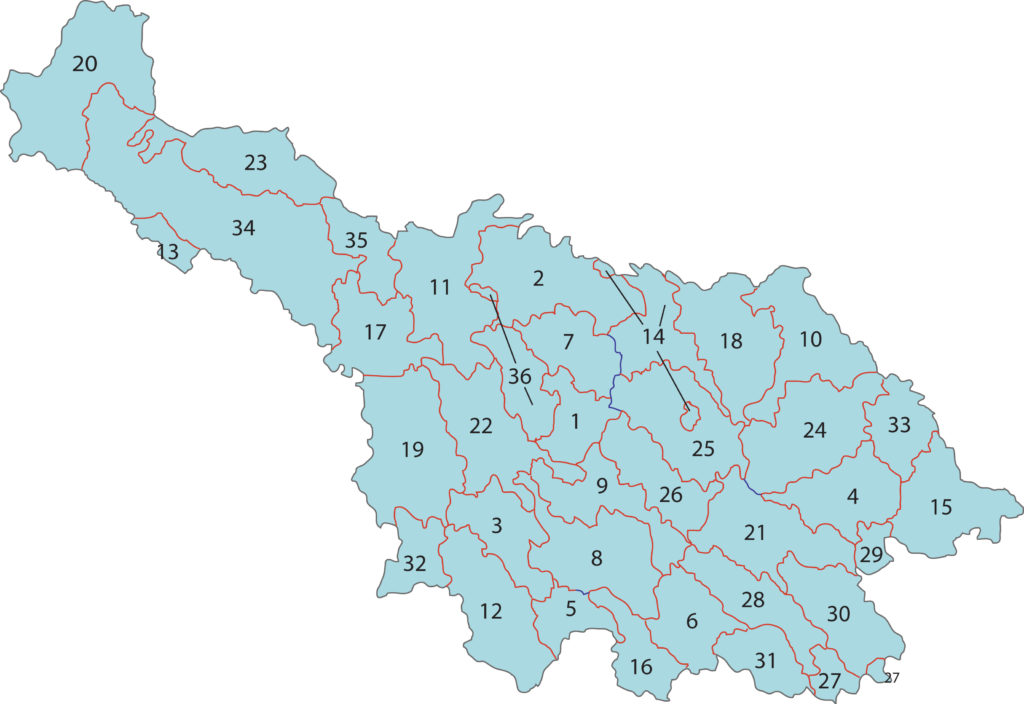

Tomás (Thomas) and his family and thereafter his descendants settled in uplands of what later became Clankee and Tullygarvey baronies in East Breifne, (Breifne Uí Raghallaigh) known in English as Breifne O’Reilly or “O’Reilly’s Country” and the Brenny. It extended about 24 miles east to west from present day Kingscourt near the Meath border to the river Owenayle (Woodford), the natural border with Leitrim. Clankee, its eastern part, about 100.6 square miles square miles of woods, drumlins, lakes and bogs, extended about ten miles south to north from present day Relagh beg townland in Moybolgue parish to part of Drumgoon parish beyond Lough Sillan and the river Annalee, and it extended about 10 miles east to west from Kingscourt to Moylett. The population of East Breifne was like that of the other Gaelic countries at that time and was small but very diverse.

An English pardon granted to an O’Reilly chief and his associates exemplified this heterogeneity. It named Philip O’Reilly, Clankee’s Gaelic lord, his immediate family members and more than eight principal followers and adherents who had different surnames including O’Clery. The McGargans, O’Clerys, O’Coyles and O’Reillys were Clankee’s leading families. The McGargans, its chiefs, possessed Moybolgue, its southern district, and O’Reillys and O’Clerys, extensive landholders, were principal families in its other districts. The O’Clerys predominated in districts which became the parishes of Killan ( Baileborough ) and Knockbride, in the heart of Clankee. The lordship’s hierarchy included a ruling family, elites comprised of subsidiary family groups (free landholders), followers who performed special services such as Gallowglasses ( mercenaries ), Church land inhabitants, family groups of professionals including Brehons (Judges), Doctúirí (surgeons, physicians), Fíle (rhymers, poets) and Ollamhs (chroniclers,historians) and a huge underclass of landless and poor inhabitants (churls). The size and composition of East Breifne’s population is not known. However, in 1442, Sir Thomas Cusacke, Lord Justice of Ireland, reported that O’Reilly forces consisted of 1,000 Kerns, 300 horsemen and 100 Gallowglasses

Tudor Conquest

Many O’Clerys were inscribed in four Fiants for pardons issued between 1533 and 1603 during the reigns of Elizabeth I and her successor, and cousin, James I. These royal pardons preserved their names for posterity and evinced a close O’Reilly and O’Clery bond as well. A substantial number of the O’Clerys listed in these pardons were of Clankee. This pardon was the earliest list recording the names of the most prominent people living in various districts. Each pardon noted a recipient’s forename and surname and sometimes his occupation and dwelling place (townland). Occupations included gentleman, horseman, kern, yeoman (independent farmer), husbandman (tenant farmer), labourer, clerks, smith, rhymer and surgeon. Horsemen ranked second to chiefs, and kerns second to none. Chiefs recruited richer landholders as horsemen and obliged poorer ones to serve as kerns. In return for military service, chiefs provided protection and patronage. A pardon excused rebellion, high treason and serious felony crimes and it enabled its recipient to obtain freedom and retain property. It also gave a measure of protection against confiscation, arrest and imprisonment, especially by local sheriffs and marshals (law commissioners) Most pardons required a recipient’s appearance at a native county court session or before a Provincial Council to post a good conduct surety. Each recipient sought a pardon as a declaration of a clean record after military or political conflict and as a receipt for having waived reimbursement for English army requisition of his cattle or horses.

Three Elizabethan pardons named a total of 21 O’Clerys. On 23rd September 1603, Queen Elizabeth pardoned Philip O’Reilly along with his many associates, this cohert included more than 20 O’Reillys, most of them gentlemen, two yeomen and five O’Clery horsemen. As recorded in Fiant 3423 the O’Clery horsemen were; Cormack Oge, of Aghillone (F), Moriertagh macTirlagh, Tirrelagh mac Gillysboy and Conogher of Keillvacknorrane (F) and Brian MacDonnell of Leare (Lear, then a Killan townland). Cormack Oge O’Clery’s placement, eighth after his chief and separate from the other O’Clerys, indaticed that he held a high position, possibly hereditary historian or chronicler.

The additional recipients’ surnames were ten O’Gullphadricks, O’Dalys, M’Symons, M’Brady, M’Cabe, O’Gowne, M’Conyne, M’Eche, M’Nicholas. O’Briody, O’Moledy, Ny Gonchoy, O’Sheridane, O’lyn, McDiermott and McKeigh.

Hearth Money Roll

The 1666 Hearth Money Roll listed householders in several parishes, grouped by townland. Although Clankee records are not extant, Castlerahan barony, which borders Clankee’s southern part, recorded O’Clerys who paid the hearth tax! these included Patrick Clery of Mullagh, Hugh Clery, Coconaght Clery, Connor Clery and 88, of Killan, a parish priest, known as a poet, and Brian O’Clery, c! 1728, of Moybolgue. Both wrote at least two poems in Irish. More then a century later, Sean O’Clery, son of Patrick O’Clery, a native of Drung parish, Tullygarvey, became known to historian John O’Donovan in Dublin. O’Donovan praised O’Clery as a fine Irish scribe and scholar. O’Clery, who transcribed ancient Irish manuscripts, traced his descent from Cucogy O’Clery, one of the Four Masters.

Penal Times

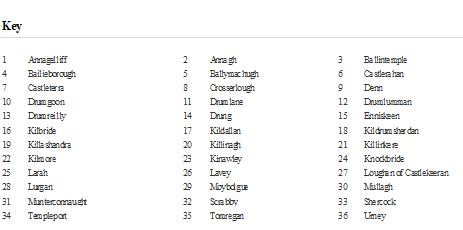

In the eighteenth century, the Gaelic Irish, harshly repressed and desperately poor, earnestly desired socio- economic advancement so many of them resorted to anglicising their surnames O’Clerys adopted the surname Clarke. The 1796 flax Growers List documented this identity change. It listed almost a dozen Clarkes in Bailieborough, Drumgoon, Enniskeen, Shercock (Killan) and Knockbride parishes. Connor Clarke and Michael Clarke, of Killan, each operated a single spinning wheel (flax spinning earnings would have augmented a family’s farm (work income)

Although the original records perished in 1922 during the Irish Civil War, the 1911 census serve as a key source for , counted, in the six parishes that were part of Clankee, a total of 293 Clarke and 242 Reilly households, most of them in Bailieborough, Killan and Knockbride. (Bailieborough was established as a separate parish in 1839 by separating 29 townlands from Killan)

Griffith’s Survey located a Reilly and three Clarke leaseholders on a Dhuish mountain hilltop in Ralaghan, site of an ancient earthen rath (ringfort). Landlord Singleton leased 28 acres to James Reilly and an adjoining 22 acres to Michael, Sarah and Francis Clarke. The Clarke families sheltered in a cluster of stuccoed dwellings along a rocky lane! In one of these cottages, Patrick Clarke, son of Andrew, son of Patrick F, was born in 1849 and his mother, Bridget, was a Lynch. This Patrick was my grandfather and he told a census taker that his family’s first language was Irish. These Reilly and Clarke nearby neighbours may well have been occupiers of an ancestor’s home place. It is not inconceivable that they descended from an O’Reilly and an O’Clery cited in the pardons and depositions. However, no local tradition about this possible link survived. I recovered this lost heritage from historical sources and shared it with our family in Ireland and America.