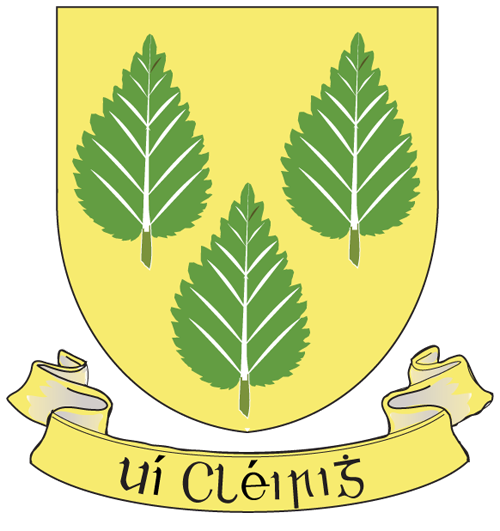

Origins

Ua Cléirigh, meaning “descendant of the scribe” is the Irish for both (O) Cle(a)ry and in many cases in Ireland, Clark(e). The surname is of great antiquity, deriving from one Cléireach of Connaught, born circa 820. Sometime between 1342 and 1348 during the Chieftainship of Niall Garbh O’Donnell, Cormac Uí Cléirigh (O’Clery), son of Eoghan Sgiamhach Uí Cleirigh from Tír Amhalghaidh (Tirawley) travelled north from Connacht to the Cistercian monastery of Assaroe in Tír Connaill.

Brehon Lawyer

Cill Barrainn Cormac Uí Cléirigh was a brehon lawyer and during his stay with the monks at Assaroe he met Matthew Uí Scingín chief ollamh to the Uí Domhnaill (O’Donnell) clan and lord of Kilbarron. Uí Scingín was much impressed by the young Cormac and he later introduced him to his only daughter whom he later married. (Matthew O’Scingín’s only son, Giolla Brighde O’Scingín died suddenly in 1382) Because the office of Ollamhs to the O’Donnells was a hereditary position, it was agreed that Cormac’s eldest son would assume the role after the death of his maternal grandfather. Thus Cormac’s son Giolla Brighde Uí Cléirigh, named after his late uncle succeeded in turn to his grandfather’s titles position and land. The land comprised of the coastal area of the parish of Kilbarron, excepting lands belonging to the Cistertian Abbey of Assaroe.

The Uí Cléirigh family remained in this position for the next three hundred years, closely allied to and related through marriage to the clan Uí Domhaill . It is perhaps important to point out that in Gaelic custom and practice land did not belong to one member of a clan but was owned in common. Other minor clans living within a district or tuath would in turn give tribute to the chief clan. The system, known as “gravelkind”, was not without fault and the rights and lives of the poorest was not much better than the lives of their counterparts in the Norman feudal system. However they were considered freemen and were tied by family and custom to their clan chieftains.

The Tudor Conquest

The late 16th Century saw the consolidation of Tudor power within England under Henry VII and with this security, his son, Henry VIII began to roll back the power of the Irish lords starting with the major Anglo-Norman families of the Geraldines. His children Edward, Mary and Elizabeth continued this policy. Added to this mix was the Reformation that would in the decades and centuries following, determine loyalties, and ultimately lead to the destruction of Gaelic Ireland.

The method of succession within the Gaelic clan system was simple in concept but fraught with dangers from all sides. Basically when the “old Chieftain” died, the Clan would gather and proclaim one amongst the top segment of the clan, a new Chief. This meant that the Chief’s own immediate sons did not necessarily inherit the Clan leadership. All offspring of a chief, whether within marriage or outside, as well as distant cousins from a common great grand father, could be considered as contenders. This situation led more times than not to a clan civil war, with factions battling it out until one or another became dominant. Often stronger neighbouring clans would become involved and place their “man” as the next Chieftain.

The Norman method of primogeniture (eldest male succession) was looked at with envy among most Gaelic chieftains who wished to secure their own immediate family’s succession and when Henry VIII offered the Gaelic Chieftains of Ireland an opportunity to give their loyalty to him, surrender their chieftainship, and take up titles of Earls of their respective territories, most did, as it also confirmed their immediate family to the succession of their Earldoms and title to their lands. As Henry’s power was weak within Ireland at this time they did not foresee the long-term effect of this policy.

Many years later when writing the Annals of Ulster Mícheál Uí Cléirigh would remark that this single decision was the first undoing of the position of the Ulster Gaelic chieftains. This all culminated in the Nine years war fought between the Gaelic Chieftains of Ulster and the successive Lord Deputies sent by Queen Elizabeth I to settle and subdue the Province of Ulster.

The end of the Gaelic order

After the defeat of the Gaelic Lords at the battle of Kinsale each chieftain separately made peace with King James and all were re-granted their earldoms. As part of the settlement they had to accept the primacy of English law and the division of their territory into counties. A Sheriff was appointed in each of the new counties with a responsibility for the law and directly reporting to the government in Dublin. In addition monastic land and property was all forfeited to the crown.

As part of this settlement 2,000 acres of land around the port of Ballyshannon was forfeited to the Crown and given to Sir Henry Folliott. It is probable that this initial grant was land taken from the Abbey of Assaroe.

The following years were difficult for the former chieftains as they saw their powers being stripped from them. Within Donegal, Niall Garbh O’Donnell was encouraged to try and replace his brother in law, the Earl Rory O’Donnell. Previous subject clans such as the Ua Dochairtaigh (O’Doherty) of Inishowen and the MacSuibhne (McSweeny) na dTuatha (Doe) were encouraged to break away from their obligations to the O’Donnells.

This new state of affairs did not rest easy with the former Gaelic Chieftains. The following years were uneasy for the Earls; they suspected that the government would arrest them on charges of treason. Hugh O’Neill was in contact with the King of Spain and was suspected of planning a new rebellion. To what extent it was true is still hotly debated among scholars of the period. In any event they decided to leave Ireland. This event became known as the “Flight of the Earls” and took place in 1607.

Their flight from Rathmullen on Lough Swilly in north Donegal was in execution more haphazard than planned and many were left behind such as Hugh O’Neill’s younger son Conn who was being fostered.

Amongst those Chieftains that left was Rory O’Donnell of Tir Conaill or Donegal. Others included his brothers Caffrey and Donal. There is no Ó Cléirigh listed in the group that left Rathmullen.

The O’Donnells were the dominant clan in Donegal to this time and the O’Clearys owed their lands and position to this family. As well as being hereditary scribes to the O’Donnells they also were herenachs (land Stewarts) to the lands attached to the Abbey of Assaroe. As a result of this event all lands belonging to the departed Gaelic nobility was forfeited to the Crown and lands within the counties of Armagh, Tir Conaill (Donegal), Tyrone, Coleraine, later united with the Barony of Loughlinsholin to become Co Londonderry (Derry), Fermanagh, Cavan and Leitrim were open to plantation.

In the general pardons list issued on behalf of King James I in 1609 is listed one named Conor O’Clerie though it does not say where in Co Donegal he was from..

The Ulster Plantation

The Ó Cléirigh clan of Kilbarron were probably left with their lands around Kilbarron intact at this stage. The government began to assemble information on the lands and dues within the counties proposed for plantation. In 1609 Lewis O’Clery head of the O’Clery clan was summoned to the Inquisition at Liffer (Lifford) to give information on the lands and leases of the O’Donnells. In reference to the lands of Kilbarron he stated.

Kilbarron parish

Herenaghs- the sept of the Cleries or freeholds

Kilbarron Parish in the said Barony contains 5 qrs. One of which is herenagh land possessed by the sept of the Cleries as herenagh who pay yearly to the Bishop of Raphoe

13s 4d rent. 6 meathers of butter and 34 of meal, one qr. named Kildonnel (Kildoney?) in possession of the said sept is wholly free from tithes to the bishop, the late abbot of Asheroe was parson and vicar of the said parish in right of his house and received 2/3 of the house in kind, the remainder being payed to the bishop, the church being maintained by both according to the same proportion.

As reward for his services to the Inquisition he was treated relatively leniently and along with his cousin Sean was granted a small estate of 960 acres in Kilmacrennan, in north Donegal. These lands consisted of the following quarters, Dromenagh, Killomastie, Dromurackan, Glaske, Tircoragh,Cragh,Derrenagh and the half quarter of Clandonnell all situated the western side of Glenswilly.

| 22 Donnell Ballach O’Galchor, Dowtagh McDonnell Ballach, Edmond Boy O’Boyle, Tirlagh Oge O’Boyle, Cahir McMalcavow (O’Boyle), Shane McTirlagh (O’Boyle), Dowatagh McGillduffe, Farrell McTirlagh Oge (O’Boyle), Loy O’Cleary, and Shane O’Cleary | 960 | 10 , 4 , 10 |

It is not clear if Lewis O’Cleary went to Kilmacrennan but in later listings for Kilmacrennan there is no mention of his name or family. There is some indication that his land grant was forfeited three years later and given to Sir Henry Gore. It seems likely that this land grant was for his lifetime only and reverted to the crown on his death.

The strategic position of Ballyshannon as a port and controlling the narrow water on the western part of the Erne river system was to valuable to leave in the hands of an Irish family. The barony of Tirhugh was however left as an area of government interest and was planted relatively lightly leaving many Irish families in continued possession of their lands.

The Abbey lands of Assaroe were forfeited to the Crown and the abbey land south of the Erne were granted to to Sir Henry Ffoliott, later created Baron Ballyshannon. Some of the O’Clery lands around Kilbarron and Drumcrin in the Parish of Inishmacsaint was granted to Trinity College, Dublin. The castle and surrounding land was granted to the Protestant Bishop of Raphoe.

The Ffolliott grant was as follows: Parish of Inismacsaint 1,034 acres

Parish of Kilbarron 1,187 acres

Parish of Drumhome 520 acres

In addition they leased Trinity College land comprising of 703 plus acres

The Ffolliott also had the manor of Dumkyn, in County Fermanagh, and their original land in Pirton, Worcestershire, England.

Tenants

The O’Clerys did remain in the parishes of Kilbarron, Drumholm and Inishmacsaint though were now tenants of the new landowners the Ffolliotts, the Established Church and Trinity College, the lands of the two latter named were those former Uí Cléirigh lands forfeited in the Ulster Plantation. The O’Clerys remained as major tenants in the coastal area in the vicinity of Kilbarron Castle until the Williamite wars but subsequently became anonymous until referred to as tithe paying tenants in the 1830s. Tithes were not payed in the major portion of the parish of Kilbarron and Drumholm as the lands were formerly church lands (Abbey Assaroe,) now owned by the Ffolliotts but archaically were due on the former secular lands in the parish which by the 17th Century were now belonging to the Established Church and Trinity College In these lands we find the O’Clerys or becoming latterly more commonly known as “Cleary”

From this time onwards Clearys were translating their name from the Gaelic “Uí Cléirigh” to O’Clery Cleary and ultimately sometimes to Clarke, the latter being the full translation into English of the name which unlike the erroneous translation of many Gaelic surnames was a proper translation of the surname.

The name Clark or Clarke has many possible origins being Anglo -Norman, English and Scottish surnames, the latter Clarke being a branch of the Clan Chattan.

Griffiths Valuation circa 1857

In Griffith’s Valuation which took place in Co Donegal in 1857 the majority of Cleary ratepayers listed lived in the parishes of Kilbarron and Inishmacsaint. The majority of these are found in the vicinity of Kilbarron castle. See map below.